This week’s blog takes a look at Roman religion. Archaeologists have discovered that the influence of Roman religion reached far and wide across Britain and took may forms.

Why was religion so important to the Romans?

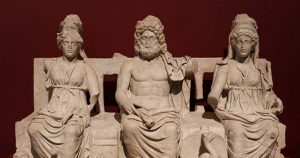

The Capitoline Triad

Religious belief permeated all aspects of Roman life: business, leisure and home life. Even war. The Romans believed in many gods and goddesses and each had its own role and particular characteristics. A request or offering, could be made to them. For example, Jupiter was the most powerful of the gods and was believed to be the protector of Rome. Jupiter’s wife Juno was associated with childbirth and their daughter Minerva, with wisdom and healing. These three gods were considered the most powerful in the hierarchy of gods and were known as the Capitoline Triad. There was also the imperial cult where Roman emperors and their families were believed to be gods.

What did Iron Age people believe and how did they worship?

Unfortunately, the Iron Age people did not record how they worshipped or write the names of their gods or spirits. They are only recognised through later Roman altar stones or dedications, which are written in Latin and give Celtic sounding names.

The practise of Iron Age religion is not clear as Roman and Greek historians did not record it in detail. People are thought to have worshipped the spirits in sacred places, such as clearings in woods. Archaeologists have found evidence of offerings made to the spirits, including weapons which were either buried in the ground or thrown into lakes and bogs.

Clearing in woodland

Julius Caesar, who was writing for a Roman audience, described head hunting, human sacrifice and cannibalism, as being part of their religious rituals. He used the word ‘Druid’ in relation to Iron Age religion, but frustratingly, did not describe the term.

What was Romano-British religion?

In the early years of Roman Britain AD43 onwards, Rome was happy to tolerate Iron Age beliefs. The absorption of local spirits into their own religion was due to Roman superstition. The Romans believed that it was important to get the local spirits on the side of the new Roman government. This acted as a unifying force across Britain and made the Iron Age people less likely to rebel.

There were regional differences in beliefs and the traditional Roman gods were more popular in urban and high status rural areas. A good example of this is Roman Bath (or Aquae Sulis as it was known). The goddess Sulis Minerva was worshipped here. Sulis was probably the Iron Age equivalent of Minerva. The central pediment of the temple in Bath had a carved stone face which can be seen at the Roman Baths museum today. It has a moustache, a strong gaze and hair made up of serpents. It is probably a fusion of the Neptune, god of the sea, Minerva and Medusa (of the famous legend).

Carved face at the Roman Baths, Bath

By the 4th century religion became more divisive as the cults of Christianity and Mithraism clashed with not only each other, but with other beliefs practised in Britain. Mithraism was a mystery religion centred on the god Mithras. It was popular amongst the Roman military and it had seven stages of initiation.

The Roman state objected to a belief in one god as it rejected the earthly power of the emperor and his supposed divine ancestors. Faiths such as Christianity and Judaism were therefore thought to be a political threat and were ruthlessly put down.

However, Christianity was made the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380 by Emperor Theodosius I, allowing it to spread further and eventually wholly replace Mithraism in the Roman Empire.

What is the evidence for Romano-British Religion in North Somerset?

Romano-British temples are known to have existed across the south west and in particular Somerset. Archaeologists have excavated temples on Brean Down and at Henley Wood, Yatton. Brent Knoll and Worlebury are also thought to have been the site of temples. Archaeological finds of ‘ritual’ objects have also been found, including an altar stone to the god Mars, from Cadbury Camp at Tickenham and a carved stone head from Steep Holm.

Brean Down Temple

Cliffs on the south side of Brean Down

Excavation of Brean Down Temple

The temple was excavated in 1957-8. It consisted of a central ‘cella’ which was the main part with an antechamber along the front. A walk-way on the north, south and west sides ran around the cella. The walls were built of limestone. Around 387- 388 AD, the temple was increased in size by lateral annexes giving it a ‘T’-shaped plan and a front porch was added. Internal doorways led to the ambulatory. The excavator thought that the temple was constructed soon after 340 AD and was in use for 25/30 years before being abandoned. The temple passed through a phase of dilapidation and squatter occupation. It was demolished around 390 AD and the building material used for a small building to the south.

Henley Wood Temple, Yatton

Interior of Cadbury-Congresbury hillfort, looking towards Henley Wood

The site in the parish of Yatton, lies close to the hillfort of Cadbury at Congresbury. In the 1960s archaeologists discovered a succession of Roman temples that had been constructed within an enclosure. This became the location for more than fifty graves of the 5th to 7th centuries, possibly the inhabitants of the fort. The excavators found a ‘Mother Goddess’ figurine and sherds of iron age pottery which indicated that the site was a sacred place of worship which stretched from the Iron Age to the Roman period.

How did Romano-British people worship?

It is thought that people worshipped as individuals, Congregational worship is associated with Christianity that came towards the end of the Roman period.

At the temple, the cella or central room was probably where the statue of the god/spirit was kept. This would only have been accessible to the ‘priest’ who looked after the temple. The surrounding walk way was used for meditation, to speak to the priest who would convey messages to the god and maybe to shelter in bad weather. There would have been an altar at the front of the temple where offerings could be left. These might include pottery, spears, brooches and coins.

For most people worship carried on as it had done in the Iron Age, the difference being that the spirit was contained inside a stone building.

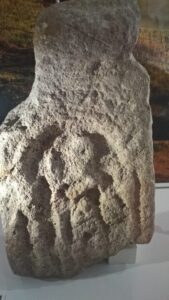

Steep Holm Head

Steep Holm carved head

The head was discovered by a member of the archaeological team excavating the medieval priory on the island in 1991. It was found out of archaeological context, lying on loose scree on a ledge above the zig zag path that ascends the island. It is made from an impure Jurassic Limestone, possibly Dundry stone. The elongated shape suggests that it may have once been placed in a niche of a building, perhaps a shrine of some sort? The gaping mouth and long nose are typical of other carved heads found across Britain.

Mother goddess from Henley Wood

Mother Goddess from Henley Wood, Yatton

This little figurine wears a torc around her neck and has a plaited band around her hair. Her eyes would have been filled with enamel or glass. Mother goddesses were popular figures within the Iron Age belief system and probably associated with fertility.

Roman Altar Stone, Cadbury Camp, Tickenham

Mars altar stone. Can you spot the figure in the centre carrying a spear?

This Romano-British relief may be a local version of a Roman god, possibly Mars or Silvanus. He is carrying a spear. It was found at Cadbury Hill, Tickenham, a small multivallate hillfort situated on a natural and commanding ridge which separates the Gordano Valley from the Somerset Levels.